Where does your commitment to human rights and against the death penalty come from?

This commitment has the same origin as my political commitment: my family background. I was born and raised in East Germany. My father was imprisoned for several years by the GDR government. Seeing the most generous person in the world incarcerated left me with a strong sense of injustice as a child.

Later, I had the chance to grow up in a democratic country. I was six years old when the Wall came down and Germany was reunited. From this experience, and from my family’s commitment, I learned that it was important to fight for democracy. I now have a seven-year-old son and I continue to fight do that he will be able to live in a state of law and a just world.

What is the history of the death penalty in Germany?

The death penalty is, of course, very closely linked to Germany’s Nazi past. The Nazis had brought the judicial system to heel. There was no separation of powers, as we know it today. In addition to the mass crimes they perpetrated, the Nazis executed a very large number of political opponents and members of the resistance. Between 1933 and 1945, an estimated 16,000 death sentences were pronounced, and 12,000 people were executed.

After the war, when the two Germanies were rebuilding, the question of the abolition of the death penalty immediately arose. In West Germany, the subject was the subject of considerable debate, and two very different political poles argued in favour of abolition. On the one hand were the social democrats, who believed that the state had no right to end a human life; on the other were right-wing parties, some of whose members hoped to escape capital punishment for war crimes committed during the Nazi period. Abolition won, by a small majority, in 1949. Since then, it has been enshrined in Article 102 of the German constitution.

And in East Germany?

Things are different. The death penalty existed until 1987, before the collapse of the regime. It was regularly pronounced and applied there. There were 231 death sentences and 166 executions during the regime. These were usually for charges of high treason. I am thinking, for example, of Werner Teske, a former Stasi [East German state security] officer, who was shot in the back of the head on suspicion of espionage and desertion. This is a very dark part of our history, which we are currently working on. After reunification, the death penalty was officially abolished throughout the country.

Is the abolition of the death penalty now being called into question?

There have always been and still are far-right populist parties that propose simplistic solutions to very complex problems. So sometimes you hear that it would be easier to execute this or that criminal. But I don’t think there is a real movement to reintroduce the death penalty in Germany.

Is the abolition of the death penalty guaranteed at the European level?

Yes, today it is a consensus in all European Union [EU] countries. In addition, the EU has also adopted a recommendation that its member states actively engage against the death penalty in non-member countries.

French lawyer Robert Badinter thinks the 21st century will see the abolition of the death penalty. Do you agree with this prediction? Is worldwide abolition possible?

Yes, I think the global trend is in that direction. In the space of 50 years, more than 100 states have abolished the death penalty, and many others are showing signs of doing so.

The question of whether global abolition is possible in the short term is more complicated. When you look at the countries that do and do not apply it, you do not find the usual divisions between liberal democracies and repressive regimes or dictatorships. Among those who still apply the death penalty, you have, for example, the United States and Japan. If these two countries took the plunge, it would make a big difference.

“In the space of 50 years, more than 100 states have abolished the death penalty, and many others are showing signs of doing so”

Have there been any significant advances lately?

There have been many advances in Africa: Sierra Leone has abolished the death penalty in 2021, Zambia and Liberia have taken steps in this direction. At the same time, in those countries that still practice it, the number of executions is steadily decreasing – although one must, of course, take into account the effect of Covid, which has prevented many trials from taking place.

In general, these developments should not be seen strictly in terms of abolition or not. There are many degrees in between: for example, the commutation of the death penalty to life imprisonment, a moratorium [a temporary suspension of executions] and so on. The most important thing right now is that a debate on the death penalty is taking place in these societies. But for this debate to take place, a certain context is needed. In Zambia, for example, until recently, children as young as eight were incarcerated because there were no public structures to deal with juvenile offenders. In countries where the death penalty is still in use, the whole social and judicial infrastructure needs to be reviewed. And any progress in the field of democracy, social progress and human rights is a victory for our cause.

Is there a risk of backsliding in some regions?

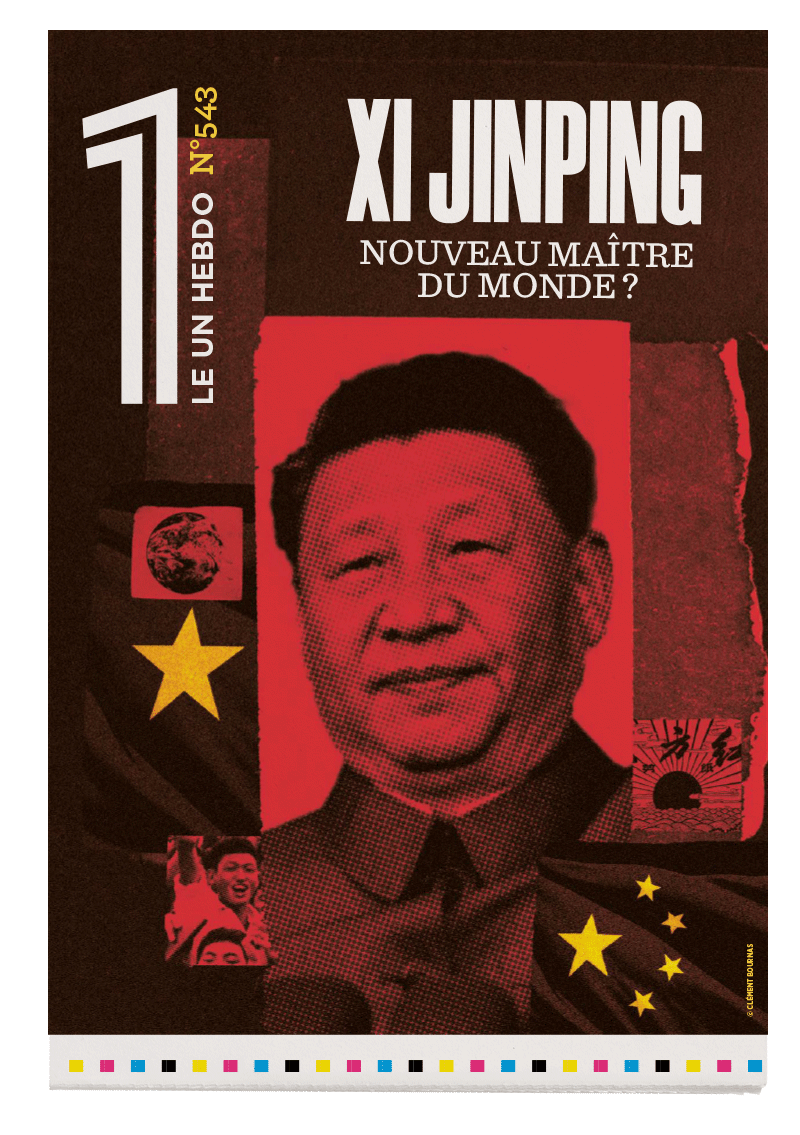

Wherever there are conflicts, wherever there are populist regimes, there is a danger. We have a very striking example in Europe: Belarus. For some time now, Belarus has included “attempted terrorist acts”, therefore alleged terrorist activities, among the grounds for death sentences. As for China, although it does not publish its figures, we know that many people are regularly executed there.

I would also like to mention the special case of “unexplained disappearances”, people whose trace we have lost, we don’t know whether they have been killed or sent somewhere. In a way, this also falls into this category. Of course, it is not a death penalty in the legal framework, but we should know that in many states, people are executed extralegally.

In the end, we always come back to the central question of whether there is a division of powers, the separation of justice and politics, but also of the executive, the legislative and the judiciary. There is a risk of a backlash on the death penalty in all countries where democracy is endangered, where the regime becomes more restrictive, and where the death penalty is going to be used as a tool of repression and deterrence. At the moment, the world is so unpredictable, marked by wars and the rise of the extreme right, that it cannot be ruled out.

As citizens, what can we do to help fight against the death penalty?

Civil society obviously has an important role to play in many ways: political activism in favour of abolition, documentation of cases, pressure on political leaders, and so on. This can also be done through films, popular culture, the commitment of artists who give visibility to the subject, etc. But it is above all up to states to support and encourage countries that going down this path and, more generally, to promote democratic efforts throughout the world.

“There is a risk of a backlash on the death penalty in all countries where democracy is endangered”

How can we argue for abolition faced with states that still practice it?

Essentially, it is up to us to say that a state should not put itself on the same level as murderers or respond in the same way. It is a matter of clearly stating that human dignity is inviolable, that we do not have the right to take anyone’s life. But there is often no point in trying to convince these countries. If I said to Saudi Arabia “what you are doing is inhumane”, they would reply that it is Sharia law and tell me not to interfere. It is very important to put pressure on countries that do not respect human rights and to push them to adhere to European law. That is the only way to help the people concerned. At the same time, we cannot refuse to deal with all the countries that have dirty hands, otherwise we would have no partners, not even the United States. It’s crucial to keep the dialogue going, and to try to make sure that respect for human rights is at the heart of bilateral and multilateral relations.

Do states and international organisations have any real room for manoeuvre?

We can already make progress through diplomacy, by ensuring that the death penalty and human rights are always broached in bilateral discussions and that in all discussions between states the issue is raised again. I also recognise that Germany, in the past and sometimes still today, does not always put human rights at the forefront of international relations. Our economic relations must respect these principles and we should also use our economic weight to exert pressure.

Take the example of China: we can reduce our trade or make it conditional on concrete demands, in this case stopping the inhumane treatment of the Uighur population. Another example: we can actively refuse to market certain products that are directly linked to the death penalty. Since 2005, the EU has adopted a regulation that limits the trade in products used in executions, such as barbiturates.

Finally, we can support and encourage countries that have not yet abolished the death penalty but are demonstrating willingness and are on the path to liberalisation. In these cases, our support will be more comprehensive. It may include political aid to transform the country into a state governed by the rule of law. This is also the purpose of the congress organised by Together Against the Death Penalty, which will be held in Berlin from 15 to 18 November 2022: we are not only inviting countries that have abolished the death penalty, but all those who show some interest in the cause, who agree to move to a moratorium or to commute death sentences to life imprisonment. By being open, we hope to be able to establish new partnerships and cooperation, and gradually advance our cause.

Interviewed by Lou Héliot