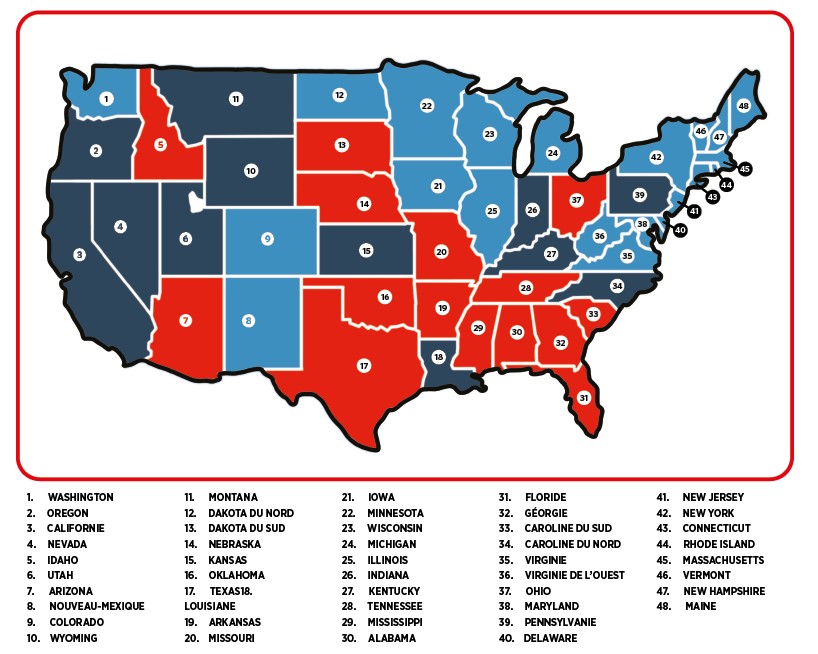

United States

An all-time high between 1990 and 2010

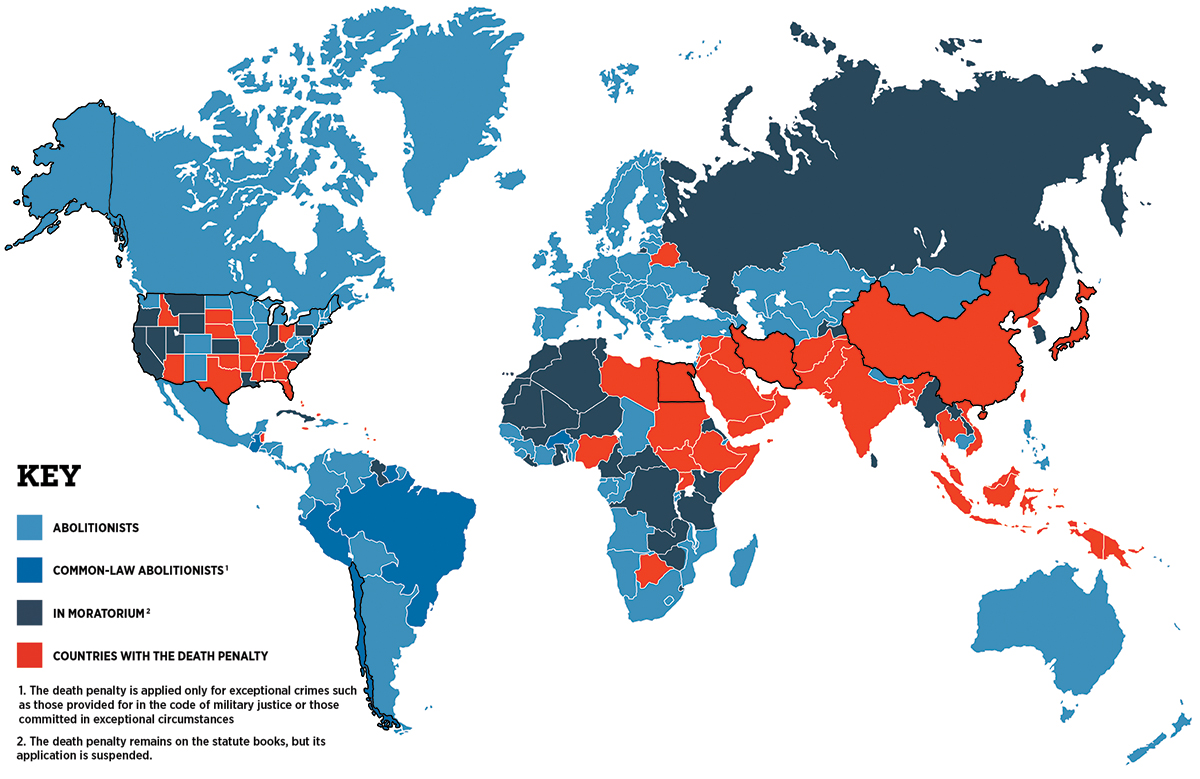

TODAY, 27 out of 50 US states have the death penalty (six of them with a de facto moratorium cancelling its implementation); 23 states have abolished it by law, such as Colorado and Connecticut, or by referendum, such as Wisconsin. In 1987 a University of Iowa law professor, David Christopher Baldus, published a study showing that a black man who killed a white man was 10 times more likely to be sentenced to death than a white man who killed a black man. The situation has improved since then, but the inequality still exists.

Over the last 30 years, there have been around 50 executions per year – one state, Texas, has accounted for half of them since the beginning of this century. But this number has been falling steadily since 2015: from 85 executions in 2000, it has gradually dropped to 17 in 2020. The same applies to the number of prisoners awaiting execution. The figure reached an all-time high between 1990 and 2010. In 2000 there were 3,593 prisoners on “death row”. Their number has also been steadily decreasing. There are currently only 2,450 of them. For these prisoners, an average of 14 years passes between the final verdict in the judicial process and execution.

Contrary to popular belief, the US Supreme Court did not abolish the death penalty in 1967. After a five-year moratorium, it abandoned the use of the death penalty in 1972 because it deemed the way that death was administered to convicts was “cruel and unusual” and therefore unconstitutional. This constituted a significant difference in a country where legalism predominates. In fact, the death penalty has never been abolished in principle at the federal level. After the court’s 1967 decision, several states maintained it in their constitutions (each state has its own constitution) while cancelling its implementation. But in 1976, Florida, Georgia and Texas had the Supreme Court recognise that the aggravating circumstances of a capital crime make the application of the death penalty admissible. Executions (by hanging, electrocution, gas chamber or lethal injection) could resume.

Sylvain Cypel

Chile

A definitive renunciation

IT took a decade of debate before a decision was finally made. On 28 May 2001, the socialist President Ricardo Lagos signed a decree abolishing the death penalty for non-political crimes in Chile, which joined the already large club of abolitionist states. His aim: to make the protection of human life a priority.

Since the fall of Augusto Pinochet’s regime in 1990 and the return to democracy, no executions had been carried out in the narrow South American country, its presidency having systematically opted for commutation to life imprisonment, with the possibility of parole after twenty or forty years of imprisonment, depending on the case. The last legal execution was in 1985. The “Viña del Mar psychopaths”, two police officers who were serial killers, were unable to obtain a pardon from the dictator at the time. At sunset one January evening, they were tied to chairs and placed with a red target over their hearts in front of 16 guards armed with Uzi submachine guns.

By signing the American Convention on Human Rights, also known as the Pact of San José, Chile pledged never to reinstate the death penalty within its borders. However, this strong commitment has not prevented the Chilean people from demonstrating for its reinstatement on the occasion of harrowing cases, such as the death of little Sophia, killed by her father in particularly atrocious conditions in 2019.

Chile had one more step to take. Until now, in its code of military justice, the country still granted itself the right to use the death penalty in wartime for various reasons, namely treason to the fatherland, rebellion, conspiracy and desertion. In November 2022, almost a century and a half after its introduction, Chile definitively renounced the death penalty in all circumstances.

MANON PAULIC

Egypt

A very political gallows

FAR from being on the decline, the death penalty has been increasingly applied in Egypt in recent years. No official statistics are available, but organisations and research centres report worrying figures. Between 25 January 2011, the day the uprising against Hosni Mubarak began, and 31 December 2020, the courts sentenced 1,670 people to death, 226 of whom are said to have been executed.

The death penalty (by hanging) can be applied for premeditated murder, rape, drug trafficking, hijacking, espionage, undermining state security and terrorism. This last charge is likely to threaten many people: particularly the Muslim Brotherhood, which was declared a “terrorist” organisation in 2014. And sometimes civilians are tried by military courts.

A death sentence is considered provisional until it has been submitted to the mufti of the republic, the highest Muslim authority in the country. The cleric’s opinion, which is purely advisory, is not made public. If the judges subsequently uphold his sentence, a convicted person can appeal to the court of cassation. In case of rejection, the head of state has 14 days to examine the case. Since becoming president in 2014, Abdel Fatah al-Sisi has reportedly never pardoned a death row inmate or commuted his sentence.

In addition to arbitrary arrests, deplorable conditions of detention and confessions extracted under torture, collective trials, rushed through, are a parody of justice. The anti-terrorist zeal of some judges reached a peak in April 2014 when the Al-Minya court in Middle Egypt sentenced 683 Muslim Brotherhood supporters to death, in the absence of most of the accused. This tragic farce did little for the country’s image abroad. Overall, two-thirds of the death sentences handed down in recent years have been for political activities.

Yet capital punishment is not an issue that mobilises Egyptians. In 2007 the National Council for Human Rights tried, without success, to launch the debate. Ironically, the Muslim Brotherhood opposed the abolition of the death penalty at the time, without suspecting that a few years later they would be the first victims of the gallows.

Robert Solé

China

Mass obfuscation

The application of the death penalty in the People’s Republic of China is shrouded in mystery. For reasons of state secrecy, no comprehensive official data has been made available by the Chinese authorities. Despite this, independent reports and investigations are unanimous and unequivocal: China alone executes more people each year than all other countries in the world combined. Amnesty International estimates that at least 1,000 people are put to death by the Chinese justice system every year, a figure that is probably underestimated. The San Francisco-based Dui Hua Foundation, the main NGO promoting human rights in China, estimates that approximately 2,000 Chinese have been put to death each year for the past five years. Twenty years ago, the figure was six times higher.

To soften its image in recent years, China has introduced measures to gradually reduce the rate of executions. In 2007 the Supreme People’s Court was finally authorised to review death sentences handed down by the country’s various courts. In 2011 and 2015, the criminal code was amended to limit the number of capital offences, including non-violent offences such as forgery. As a result, among the 46 offences that still carry the death penalty, murder and drug trafficking are targeted by the judiciary as priorities.

Despite this progress, China remains relentless in its application of the death penalty, which is widely supported by the public. Polls by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, an institution under Communist Party control, nevertheless point to an erosion of this support, estimated at 95 per cent in 1995 and 68 per cent in 2008.

In addition to the hundreds of death sentences handed down each month, the Chinese judicial system is also notable for its cynicism: the still warm bodies of the condemned are handed over to surgeons in charge of harvesting organs to feed a vast system of transplants on demand. This practice, acknowledged by a state media outlet in 2009, represented 65 per cent of the 10,000 annual transplants performed in China. A political weapon at the service of the government, the death penalty followed by organ harvesting was first used in the 2000s against members of Falun Gong, a religious community whose growth concerned the authorities, then applied to Uighur convicts beginning in 2017.

FLORIAN MATTERN

Japan

Badly treated convicts

Japan executes few people and does so with little publicity. The only exception is the 2018 hanging of 13 members of the Aum Shinrikyo sect, responsible for the sarin gas attack in the Tokyo underground. In normal times, the number of executions is much lower: 3 in 2019 and 2021, and 1 in 2022 for a total of 98 since the beginning of the century. The death penalty is almost always pronounced for murders that were particularly violent. The law provides for the punishment to be carried out within six months of the conviction. However, dozens of death-row inmates live in uncertainty and anxiety for a long time. Their confinement on death row can last for decades. This was the case for the 86-year-old boxer Iwao Hakamada, sentenced for a quadruple homicide in 1968. He was released in 2018 after a half-century of legal battles to prove his innocence, but the Supreme Court overturned that decision two years ago, opening the door to reincarceration.

The United States and Japan are the only liberal democracies that have the death penalty. It is not so much famous for the number of executions as for the way the judicial system mistreats its criminals. The daily life of a death-row inmate is an ordeal: locked in a 6-square metre cell with day and night lighting to prevent suicide, he or she only learns of the date of his or her execution in the morning of the event. The family is informed once the body is in the morgue.

Despite the madness frequently caused by the conditions of detention, 80 per cent of the public vote in favour of maintaining the death penalty every year. The ritual is immutable: hands behind the back, wrists handcuffed and blindfolded, the condemned advances towards the person who will put the rope around his or her neck. Once on the trap door that is to give way, three guards simultaneously press three buttons, only one of which opens the floor.

FLORIAN MATTERN

Iran

A Record Number Of Executions

A recurring theme in Iranian cinema, as evidenced by Saeed Roustayi’s Just 6.5 and Ali Abbasi’s Holy Spider, the death penalty also occupies a major place in the Islamic Republic’s judicial system. The reason why the national film industry has so often taken up this issue is that Iran is the country which, in proportion to its size, executes the most people in the world. Whether it is for murder, drug possession and trafficking or simply drinking alcohol, the death penalty is applied relentlessly. But while the number of executions has been falling for several years (743 in 2014 and 246 in 2020), the trend seems to have reversed in recent months with 314 cases recorded in 2021. Without official statistics from Tehran, international NGOs believe that these figures are not representative.

In the case of murder, Iranian law applies a principle of reparation (qisas) that gives the victim’s family a choice: to request the death penalty or to forgive the criminal in exchange for financial compensation or “blood money” (diya). While murder (51 per cent) and drugs (42 per cent) accounted for most convictions in 2021, the death penalty is also used as a weapon to subdue Iran’s ethnic minorities. Baluchis, Kurds and Ahwazi Arabs are the main targets of this repression, often cleverly disguised under accusations of “enmity against God”. Between 2010 and 2020, 129 people from these minorities were executed for this reason.

Finally, Iran is notable for its almost systematic use of torture to extract confessions before unfair trials and its regular conviction of minors. Despite international law, the Iranian judiciary has, since 2010, convicted and executed more than 60 people who were minors at the time of the offence.

FLORIAN MATTERN